Human activity has altered an ocean-wide law of nature

In a worldwide collaboration, environmental scientists assessed the even distribution of aquatic biomass among size classes, from bacteria to whales, for the first time on a global scale. Their quantification of human impact reveals a dramatic shift in one of the most significant scale patterns in nature.

Policymakers are currently gathering in Glasgow for the 26th UN Climate Change Conference, and mere weeks ago, the UN Biodiversity Conference took place. The prominence of these international conferences is testimony to the growing urgency of human influences on climate and biodiversity. However, the relation to biomass, or total mass of all organisms, and anthropogenic effects thereon is still largely unexplored, especially in the context of the oceans, which cover the vast majority of our planet. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences in Germany, Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals in Spain, Queensland University of Technology in Australia, Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, and McGill University in Canada have utilized developments in ocean observation and meta-analyses to reveal that human actions have already had a massive impact on the larger oceanic species and fundamentally altered one of life’s largest scale patterns – a pattern covering the entire ocean’s biodiversity, from bacteria to whales. Their latest research findings were published in the current issue of Science Advances.

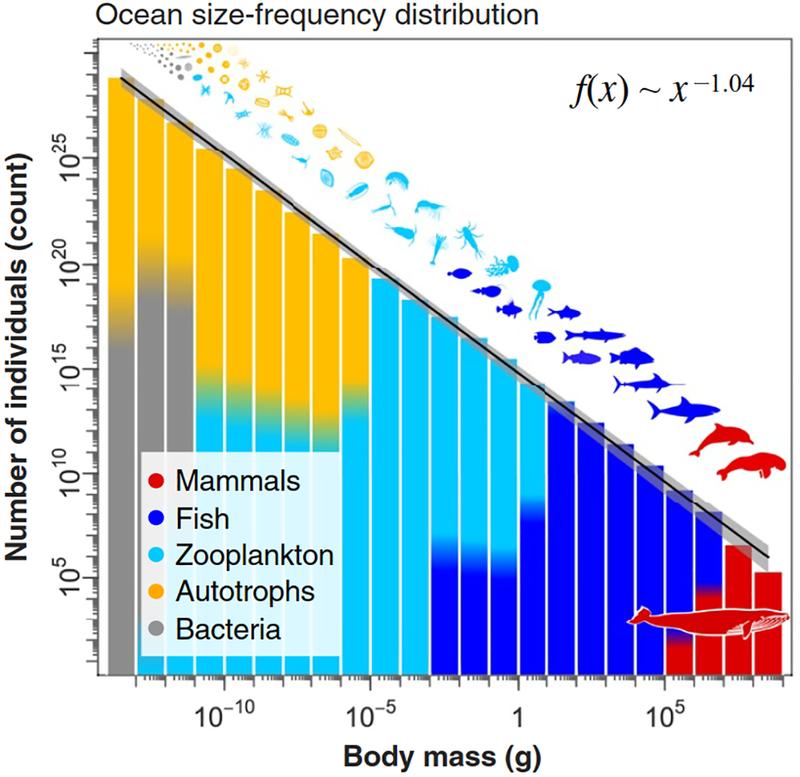

Measurements of marine plankton abundance from the 1970s led researchers at the time to presume that roughly equal amounts of biomass occur at all sizes: although bacteria are 23 orders of magnitude smaller than a blue whale, they are also 23 orders of magnitude more abundant. This size-spectrum hypothesis has since remained unchallenged, even though it was never verified on a global scale. The authors set forth to evaluate this long-standing hypothesis across all ocean life for the first time. They employed historical reconstructions and marine ecosystem models to estimate biomass before industrial activities (pre-1850) and compared this data to the present-day. “It was a struggle to adequately compare these measurements spanning such a massive difference in scale” recalls Alexander von Humboldt research fellow Dr. Ian Hatton, lead author of the study. “While small aquatic organisms are estimated from more than 200,000 water samples collected across the globe, larger marine life can cross whole ocean basins and needs to be estimated using entirely different methods”.

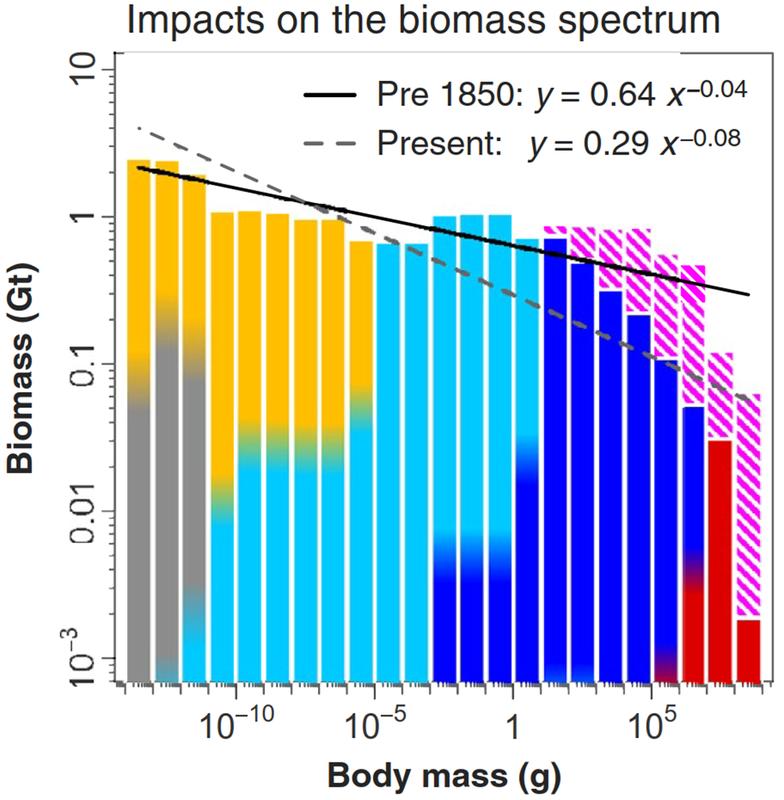

Their approach allowed them to differentiate 12 major groups of aquatic life over roughly 33000 1° grid points of the entire ocean. Evaluating the “pristine” ocean conditions (pre-1850) largely confirmed the original hypothesis: there is a remarkably constant biomass of approximately 1 gigaton in each of 23 size classes, each spanning an order of magnitude. However, there are exceptions at either extreme. While bacteria are abundant in the cold and dark parts of the ocean, the largest whales are relatively rare, thus marking a departure from the original hypothesis.

In contrast with a near-constant biomass spectrum in the pristine ocean, an examination of the spectrum at the present time, unveiled a novel perspective of human impacts on ocean biomass. While fishing and whaling only account for less than 3 percent of human food consumption their effect on the biomass spectrum is devastating: large fish and marine mammals such as dolphins have experienced a biomass loss of 2 Gt (60% reduction), with the largest whales suffering an unsettling almost 90% decimation. The authors estimate that these losses already outpace potential biomass losses even under extreme climate change scenarios.

“Humans have certainly become the top predator of the marine ecosystem, but it seems likely that we have impacted the system much more than merely removing the largest fish. Our cumulative influence over the last 200 years has diverted possibly as much as two orders of magnitude more energy than the fish that have been eliminated”, notes Dr. Hatton. This implies that humans have not merely replaced oceanic top-predators but largely altered the flow of energy through the marine ecosystem. These results have quantified a major impact of humanity on the distribution of biomass across size ranges, highlighting the degree to which anthropogenic activities have altered life at the global scale.

Wissenschaftlicher Ansprechpartner:

Dr. Ian Hatton

mailto:i.a.hatton@gmail.com

Originalpublikation:

Ian A. Hatton, Ryan F. Heneghan, Yinon M. Bar-On, and Eric D. Galbraith

The global ocean size-spectrum from bacteria to whales

Science Advances • 10 Nov 2021 • Vol 7, Issue 46

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abh3732

Ähnliche Pressemitteilungen im idw