Calcium reduces CO2 emissions from Arctic soils through mineral formation

A new study in the journal Environmental Science & Technology shows that the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) from Arctic soils is significantly reduced by calcium. The Leibniz Center for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) led the study, which demonstrates the potential of calcium to bind CO2 in mineral structures.

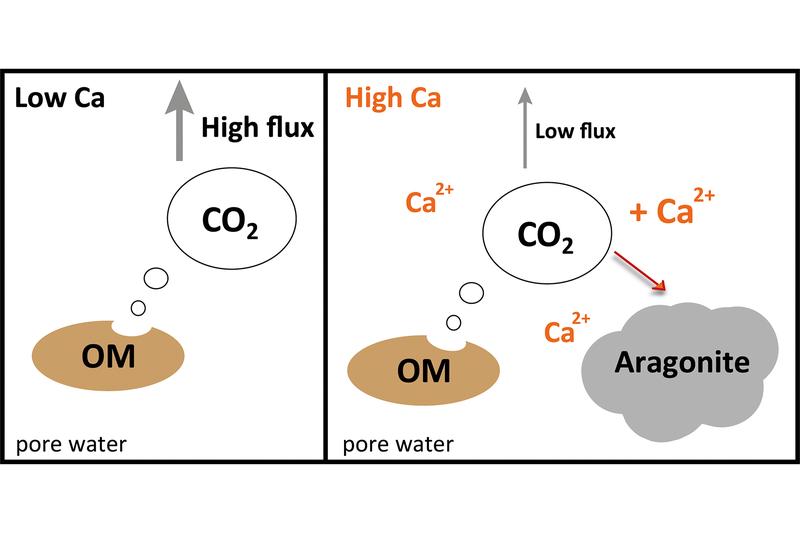

Soils in Alaska that are either poor or rich in calcium were investigated. The investigations showed that increasing the calcium content significantly reduces CO2 emissions: 50 percent in calcium-poor soils and 57 percent in calcium-rich soils. The reason: calcium promotes the formation of the mineral aragonite, which binds CO2 and thus prevents the release of this greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. The results could contribute to new approaches in dealing with the consequences of global warming, especially in the sensitive Arctic regions, which are particularly at risk from climate change.

Calcium reduces CO2 release - through the formation of aragonite

As temperatures rise, the permafrost soils in the Arctic are increasingly thawing. This not only releases large amounts of organic carbon, but also increases the calcium concentration in the soil. The study shows that this calcium release leads to the formation of aragonite - a mineral consisting of calcium and CO2. This retains CO2 in the soil, which would otherwise escape into the atmosphere.

"The ability of calcium to bind CO2 through the formation of aragonite is a surprising discovery and shows how important nutrients such as calcium can be for climate change," says Prof. Joerg Schaller from ZALF, the leader of the study. "The results open up new perspectives for the integration of these processes into global and local carbon models."

Long-term effects on climate change

The Arctic is particularly vulnerable to the consequences of climate change, as temperatures there are rising twice as fast as the global average. The release of CO2 from thawing permafrost soils could further accelerate climate change. However, the new study shows that calcium has the potential to at least partially slow down this process. The researchers are now calling for further field experiments to validate these results and integrate the process into climate models.

"Our results represent a first step. However, it remains to be investigated how stable these calcium-mineral compounds are over long periods of time and which factors influence their effectiveness," adds Prof. Schaller.

Future research perspectives

The results of the study could also be of significance beyond the Arctic: similar processes are also taking place in other regions with calcium-rich soils. In the long term, it would be conceivable to develop strategies to reduce CO2 emissions through the targeted enrichment of soils with calcium. "This could be a valuable approach to tackling the global challenge of climate change," says Prof. Schaller.

Project partner:

Cornell University, USA

University of Bayreuth, Germany

Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Germany

Leibniz Center for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF), Germany

Funding information:

The project is funded by the German Research Foundation under the reference DFG SCHA 1822/12-1.

Wissenschaftlicher Ansprechpartner:

apl. Prof. Jörg Schaller

Research Area 1 "Landscape Functioning"

Working Group: Silicon Biogeochemistry

T +49 (0)33432 82-137

F +49 (0)33432 82-280

Joerg.Schaller@zalf.de

Originalpublikation:

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.4c07496

Ähnliche Pressemitteilungen im idw