Rapid surge in global warming mainly due to reduced planetary albedo

In 2023, the global mean temperature reached a new high of almost 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to the preindustrial level. Seeking to identify the causes of this sudden rise has proven a challenge for researchers. After all, factoring in the effects of anthropogenic influences like the weather phenomenon El Niño and natural events, can account for a major portion of the warming. But doing so still leaves a gap of roughly 0.2 degrees Celsius, which has never been satisfactorily explained. In the journal Science, a team led by the AWI puts forward a possible explanation for the rise in global mean temperature: our planet has become less reflective because certain types of clouds have declined.

“In addition to the influence of El Niño and the expected long-term warming from anthropogenic greenhouse gases, several other factors have already been discussed that could have contributed to the surprisingly high global mean temperatures since 2023,” says Dr Helge Goessling, main author of the study from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI): e.g. increased solar activity, large amounts of water vapour from a volcanic eruption, or fewer aerosol particles in the atmosphere. But if all these factors are combined, there is still 0.2 degrees Celsius of warming with no readily apparent cause.

“The 0.2-degree-Celsius ‘explanation gap’ for 2023 is currently one of the most intensely discussed questions in climate research,” says Helge Goessling. In an effort to close that gap, climate modellers from the AWI and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) took a closer look at satellite data from NASA, as well as the ECMWF’s own reanalysis data, in which a range of observational data is combined with a complex weather model. In some cases, the data goes back to 1940, permitting a detailed analysis of how the global energy budget and cloud cover at different altitudes have evolved.

“What caught our eye was that, in both the NASA and ECMWF datasets, 2023 stood out as the year with the lowest planetary albedo,” says co-author Dr Thomas Rackow from the ECMWF. Planetary albedo describes the percentage of incoming solar radiation that is reflected back into space after all interactions with the atmosphere and the surface of the Earth. “We had already observed a slight decline in recent years. The data indicates that in 2023, the planetary albedo may have been at its lowest since at least 1940.” This would worsen global warming and could explain the ‘missing’ 0.2 degrees Celsius. But what caused this near-record drop in planetary albedo?

Decline in lower-altitude clouds reduces Earth’s albedo

The albedo of the surface of the Earth has been in decline since the 1970s – due in part to the decline in Arctic snow and sea ice, which also means fewer white areas to reflect back sunlight. Since 2016, this has been exacerbated by sea-ice decline in the Antarctic. “However, our analysis of the datasets shows that the decline in surface albedo in the polar regions only accounts for roughly 15 percent of the most recent decline in planetary albedo,” Helge Goessling explains. And albedo has also dropped markedly elsewhere. In order to calculate the potential effects of this reduced albedo, the researchers applied an established energy budget model capable of mimicking the temperature response of complex climate models. What they found: without the reduced albedo since December 2020, the mean temperature in 2023 would have been approximately 0.23 degrees Celsius lower.

One trend appears to have significantly affected the reduced planetary albedo: the decline in low-altitude clouds in the northern mid-latitudes and the tropics. In this regard, the Atlantic particularly stands out, i.e., exactly the same region where the most unusual temperature records were observed in 2023. “It’s conspicuous that the eastern North Atlantic, which is one of the main drivers of the latest jump in global mean temperature, was characterised by a substantial decline in low-altitude clouds not just in 2023, but also – like almost all of the Atlantic – in the past ten years.” The data shows that the cloud cover at low altitudes has declined, while declining only slightly, if at all, at moderate and high altitudes.

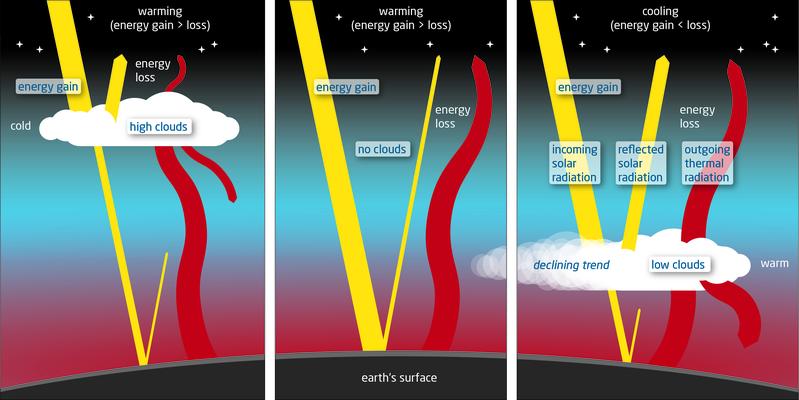

The fact that mainly low clouds and not higher-altitude clouds are responsible for the reduced albedo has important consequences. Clouds at all altitudes reflect sunlight, producing a cooling effect. But clouds in high, cold atmospheric layers also produce a warming effect because they keep the warmth emitted from the surface in the atmosphere. “Essentially it’s the same effect as greenhouse gases,” says Helge Goessling. But lower clouds don’t have the same effect. “If there are fewer low clouds, we only lose the cooling effect, making things warmer.”

But why are there fewer low clouds? Lower concentrations of anthropogenic aerosols in the atmosphere, especially due to stricter regulations on marine fuel, are likely a contributing factor. As condensation nuclei, aerosols play an essential part in cloud formation, while also reflecting sunlight themselves. In addition, natural fluctuations and ocean feedbacks may have contributed. Yet Helge Goessling considers it unlikely that these factors alone suffice and suggests a third mechanism: global warming itself is reducing the number of low clouds. “If a large part of the decline in albedo is indeed due to feedbacks between global warming and low clouds, as some climate models indicate, we should expect rather intense warming in the future,” he stresses. “We could see global long-term climate warming exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius sooner than expected to date. The remaining carbon budgets connected to the limits defined in the Paris Agreement would have to be reduced accordingly, and the need to implement measures to adapt to the effects of future weather extremes would become even more urgent.”

Wissenschaftlicher Ansprechpartner:

Sciene:

Dr Helge Goessling

Phone: +49(0)471 4831 1877

E-Mail: helge.goessling@awi.de

Originalpublikation:

doi: 10.1126/science.adq7280

Weitere Informationen:

https://www.awi.de/en/about-us/service/press.html

Ähnliche Pressemitteilungen im idw