Hormones determine whether plants form partnerships with fungi

New study deciphers how plants control partnerships with fungi

How do symbioses between plants and fungi develop? How do plants decide whether or not to enter into a partnership with fungi? The team of Prof. Dr. Caroline Gutjahr, Director at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology in Potsdam, is shedding light on the underground partnership of plants. In particular, her team discovered what happens to a symbiosis when the plant produces stress hormones. Their research could contribute to a new agriculture in which plants and fungi are considered as partners.

A harmonious team

Right under our feet, hidden in the ground, there is a complex network of relationships: almost all plants live in close symbiosis with fungi. These fungi do not form the classic mushroom fruiting bodies that we know from forests and in some cases like to eat. They form an extensive network of fine threads, also known as hyphae, that permeate the soil. In just one cubic centimeter of soil, the hyphae of the fungi can reach a length of up to 100 meters. While many fungi break down dead material in the soil, there are specialized species that live closely with plants and depend on photosynthesis products from living plants. In return, they supply the plants with water and mineral nutrients. This exchange system has existed for hundreds of millions of years and is essential for many land plants.

One plant hormone suppresses the symbiosis, another promotes it

Arbuscular mycorrhiza is a particularly intimate form of symbiosis in which the plant allows the hyphae of the fungus access into its roots and even its cells. Over the course of evolution, it has developed into one of the most intimate interactions between living beings. The close partnership between plants and fungi, in which water and nutrients are exchanged, is already pre-programmed in their genetic code. But under certain conditions, plants reject the symbiosis with fungi.

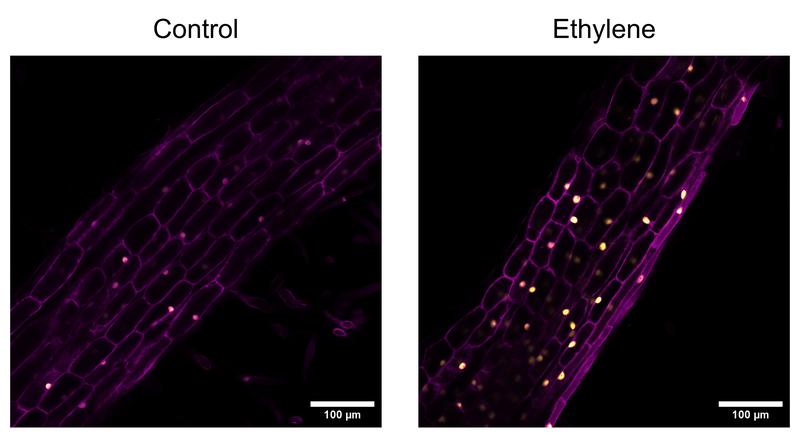

Prof. Caroline Gutjahr and her team at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology in Potsdam are investigating what exactly happens in the roots of a plant when it enters or rejects symbiosis with a fungus. Their finding: Also in plants, hormones play an important role when entering into a partnership. “For about 40 years, we have known that the gaseous plant hormone ethylene, which is produced when plants are under stress, such as being flooded, inhibits the symbiosis between plants and fungi,” explains Gutjahr. ”Now we have learned which processes take place in the plants and how various plant hormones interact. Finally, we know what happens when plants decide for or against this partnership.”

Experiments by the two first authors Debatosh Das and Kartikye Varshney showed that, contrary to common belief, ethylene does not trigger a defense response by the plant immune system against the fungus. Instead, the plant hormone boosts the accumulation of a central regulatory protein called SMAX1. This is able to suppress a number of plant genes that are responsible for the formation of the symbiosis. Thus, when environmental conditions are unsuitable, the plant produces a hormone that inhibits its symbiosis genes. The formation of the symbiosis is reduced or no longer allowed. If conditions change, other hormones gain control over the protein, initiate its degradation and thus switch the symbiosis genes back on. The plant is open to the partnership.

In collaboration with David C. Nelson's team at the UC Riverside in California, the authors were also able to show that ethylene also promotes the accumulation of SMAX1 in plants that have lost the ability to form symbioses with fungi. The significance of this discovery thus extends beyond plant-fungus symbiosis. It will be exciting to explore the role of this phenomenon outside of symbiosis in the future.

Understanding how plants regulate their symbiosis with fungi under stress conditions could provide information on how to breed crops that form beneficial partnerships with fungi even under changing stress or climate conditions. In the future, this knowledge could help to ensure that plants continue to be supplied with sufficient water and nutrients under new climatic conditions and that harvests are secured.

Wissenschaftlicher Ansprechpartner:

Prof. Dr. Caroline Gutjahr

Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology

Tel. +49 331 567 8202

gutjahr@mpimp-golm.mpg.de

Originalpublikation:

Debatosh Das, Kartikye Varshney, Satoshi Ogawa, Salar Torabi, Regine Hüttl, David C. Nelson & Caroline Gutjahr

Ethylene promotes SMAX1 accumulation to inhibit arbuscular mycorrhiza symbiosis

Nature Communications, 27th February 2025,

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57222-w

Weitere Informationen:

https://www.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/2724220/dept_9

Ähnliche Pressemitteilungen im idw